Recently, my little brother, Rich, and I entered into an interesting partnership. And during the time we were considering whether to do so, both Rich and I consulted with our father. And in comparing notes, my brother and I found that we were both asked the same questions:

“Do you trust him?” my father asked.

“Yes,” I replied.

“Do you love him?”

“Yes,” I replied again.

“Then do it,” he said, “Everything else will work out fine.”

In this conversation, my dad was brief and to the point. If the time elapsed was more than one minute, I will be shocked. My pop only had two questions – one about trust and the other about love. Never having been a man of many words and certainly never having been a touchy-feeling type guy, he assumed that the two question eight-word piece of advice was enough and it would be all that I would need. And odd as it may sound, it was.

But it was only odd to me. Clearly, it was not odd to him. For, as I sat next to my dad listening to those two questions and watching him deliver that very brief message, it became strangely clear that this wasn’t the only time that he had used this advice.

Throughout the next several weeks, as my brother and I cinched our partnership (keeping our dad apprised of the smaller subsequent decisions and choices we were making), my dad began opening up about the times that those two poignant questions guided him.

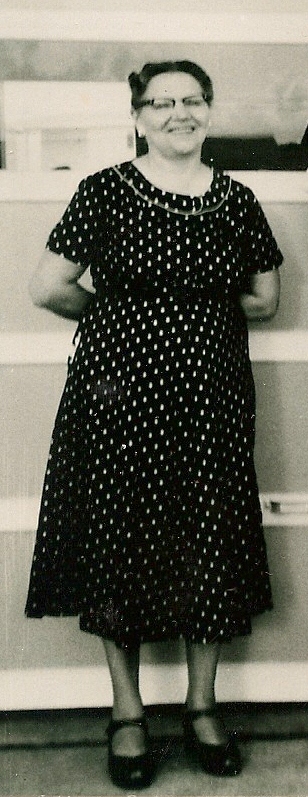

Should he marry my mother – the love of his life – and the love of ours? Yes. Should he take a risk and move his family to a great new frontier called Florissant? Yes. Should he listen to the advice from his father and take a job with a company formerly called Union Electric – now Ameren UE? Yes. Should he, himself, enter into all types of adventures and mis-adventures with his own brother, Bud – his dearest and lifelong best friend? Yes.

With love in his back pocket and trust at his side, he had no fear of his decisions. He just didn’t. He still doesn’t. The outcome of his decisions may not always have been as planned, may not always have been perfect, and may have led down new and unexpected paths, but with love and trust, he always felt that his decisions were . . . correct . . . right . . . just. Where some may have fear, he had confidence. And at the moment he was asking me his two greatest questions, he wanted me to be confident, to have no fear.

When my father asked me if I trusted my brother, he made the term . . . the idea . . . seem so simple. He didn’t want frivolous conversation from me. He didn’t want a lengthy discussion on trust, the origins of trust, and the positive benefits of trust. He wasn’t planning on spending hours and days introducing the concept of trust and pondering its definition with me. He wanted me to answer his question with a brief but confident yes or no. He really didn’t want me to discuss the degree to which I trusted my brother or any reasons why I should or should not trust him or the dangers of doing so. In fact, I think he was hoping that I wouldn’t speak, rather simply move my head yes or no – preferably yes, which I did.

When he asked me if I loved my baby brother, the same premise applied. Yes or no. Did I love him? My pop didn’t want to know the details that could have been attached to that question. He didn’t want to know any challenges surrounding it. In fact, I think that had I begun some type of discussion when my pop asked that question, he may have given me the awe-inspiring, dad-blaster ‘no time for talking’ look – the look that fathers use to pretty much stop space and time – in order to refocus me. He just wanted me to give him that one word answer, again with confidence – which was yes.

In less than one minute, with eight words in two questions, my pop did it again. It was masterful advice in the blink of an eye. He didn’t say it this way, but I definitely heard: Trust those you love . . . and love those you trust . . . everything beyond will fall in place.

His confidence in knowing that if I had trust and if I had love, then I should have no fear was moving. And my dad has been right. My brother and I are having the time of our lives – and couldn’t be happier with our decision.

I know that I, like my father, will keep those two questions handy. And as I face complicated, challenging decisions in the future, I know that – like him – I will hope that those eight words give me the same type of guidance that they have done for my dad.

But I do have to chuckle.How in the world am I ever going to meet that standard! Heck, 1000 words isn’t always enough for me to convey whatever it is that I want to convey. Well . . . at least I have a target!